The famous author/translator, Edith Grossman, passed away in September this year. Ms. Grossman’s translation of Don Quixote is considered one of the finest English-language translations of the Spanish novel, ever. Some esteemed critics dubbed her “the Glen Gould of translators, because, she too, articulated every note.” In a speech in a tribute to the Spanish author, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, she shared her method:

“Languages trail immense, individual histories behind them, and no two languages, with all their accretions of tradition and culture, ever dovetail perfectly … A translation can be faithful to tone and intention, to meaning. It can rarely be faithful to words or syntax, for these are peculiar to specific languages and are not transferable.”

For my English translation of Vidagdha Madhava, the Edith Grossman approach to tackling Rupa Goswami’s spiritual drama proved an invaluable tool. “Fidelity is our noble purpose,” says Edith Grossman, and, as she points out above – insight into the culture and tradition of the refined subject to be translated is very important.

Case in point, when a Sanskrit word has different meanings (and that’s often), the right word for the context is easily derived with a little cultural insight. For instance, the customary namesake, ‘Arjundas,’ meaning, ‘Arjun’s servant,’ is adopted in honour of the illustrious warrior, Arjun. Arjun also means ‘silver*,’ but ‘silver-servant,’ isn’t the idea. Again – ‘Arjundas Adhikari’ in English is, ‘Master Arjundas,’ where ‘adhikari’ is a nominal title. But although ‘adhikari’ does also mean, ‘government’, “A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna translated into English by the silver-servant government,” obviously confuses, while “A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna translated into English by Master Arjundas,” makes more sense.

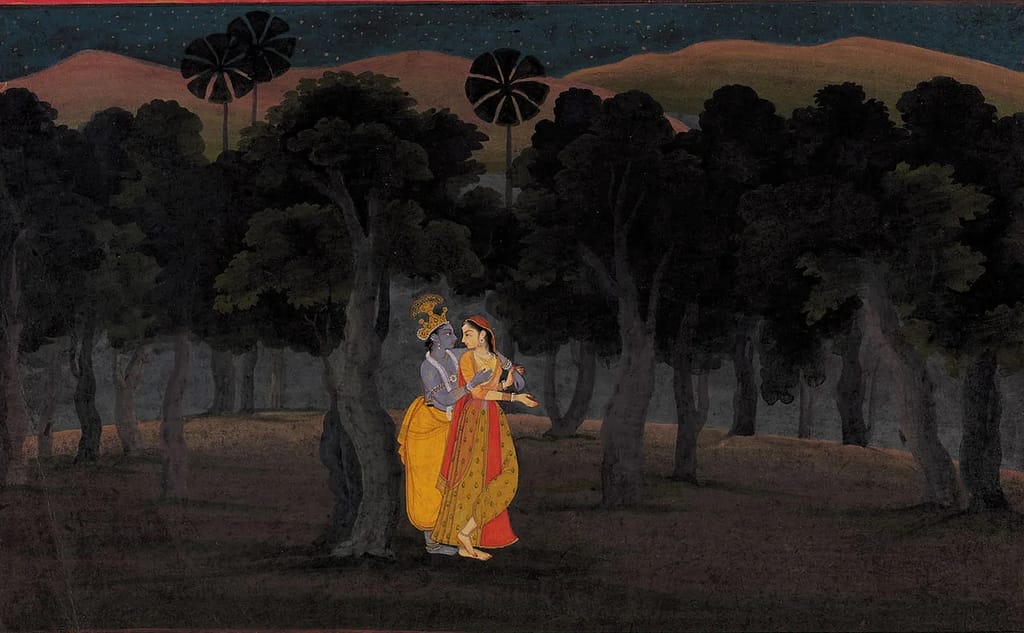

Then, how to render the marvellous poetic allusions which embellish the Vidagdha Madhava by Rupa Goswami, illustrates this further. Nods to the wonders of nature abound in Vidagdha Madhava, but the most striking allusions are to tropical efflorescences, colourfully conveying the fairness of a glance, an eye, a face, a smile or slender limb. A ‘lotus-eye,’ ‘soft, lotus-glance,’ a ‘lotus-petal hand,’ for instance, or, ‘the gentle creeper of an arm,’ ‘the jasmine-fragrance of a smile,’ ‘the blooming lily of love,’ ‘the blue-lotus sheen of a complexion,’ come to mind, and the literal sense DOES work in translation, BUT NOT ALWAYS. An evaluation has to be made as to how best a particular allusion is to be sensibly matched. To wit, I consider, ‘slender arms,’ preferable to, ‘creeper-like arms,’ and I’d say a mention of ‘lotus-eyes,’ is fine to keep.

Thus, accessibly translating an Indian spiritual drama like Vidagdha Madhava involves critical judgement: the assessment of cultural differences, religious particulars, value specifics, word-meanings and popular metaphors, all to enable a play, right for performance anywhere. The great thing about Hindu drama dialogue – as with any great dialogue – is how the characters’ speeches are acutely responsive. If the translation’s not right, though, that flow won’t be re-iterated. It would be terribly unfortunate to have misgivings about Rupa Goswami’s playwrighting skills where the problem is, in fact, a dearth of insight into a subtle language and culture.

Arjundas Adhikari

*’Argent’ is French for ‘money’, ‘argent’ being derived from ‘arjun.’