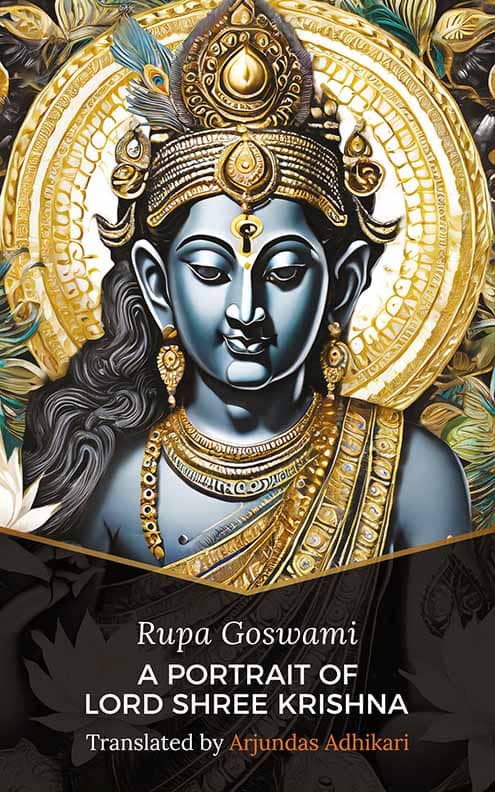

The word ‘vidagdha’ means ‘masterful’, or ‘resourceful’, while ‘Madhava’ refers to Krishna where He is depicted in a portrait. Hence, the translation of the title Vidagdha Madhava is: A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna where ‘Shree’ is an honorific indicative of grandeur. A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna was written in 1532 in India, just prior to colonial rule.

A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna is actually Rupa Goswami’s dramatisation of 12th-century poet Jayadev’s Gita Govinda. It is exceptional in the way the chief hero of the timeless sacred books of India, the incarnation of the all-pervading Lord Vishnu, the ’cause of all causes’ and original Person, is presented to us on the stage up close and personal. The work conforms to the standard structure of a Sanskrit drama, (a flourishing genre in medieval and early modern India) and, along with its counterpart Lalita Madhava, its impact was to usher in a renaissance of interest in the ancient Krishna legend, and put Him centre-stage for worship (as it were).

Rupa Goswami himself – erudite, multi-lingual and of royal heritage – had been commandeered to work as chief minister for the Sultan of Bengal, but when he met Shree Chaitanya, the luminary who spear-headed the great 16th-century revival of Radha-Krishna worship, he managed to disengage himself from government work and became dedicated to demonstrating the primacy of Krishna worship as proscribed in the Vedas (the historical and philosophical holy books of India). His scholarly credentials are well-credited, and he was popularly regarded as a great mystic. He gave up all personal possessions, and encouraged others to devote themselves to Radha and Krishna, and was said to have been imbued with an exquisite but unbearable sense of Krishna’s absence.

Some have conjectured, considering the length of Vidagdha Madhava, that the acts may have been staged separately on consecutive evenings, perhaps during gatherings that would have occurred during festivals. In any case, Bharata Muni’s exhaustive 1st century CE handbook to dramatury – the Natyashastra – bears testimony to how developed the culture of stagecraft was even in ancient India. There can be no question that the play’s prime purpose was for something other than being enacted on a stage. The idea that Rupa Goswami’s Vidagdha Madhava, indeed any Sanskrit Hindu drama, was written just to read, or as an anthology of poetry, is ludicrous in view of how precisely they all correspond with the entirely performance-oriented Natyashastra directives. In my opinion, that notion might come from the sort of cultural snobbery endemic in Victorian times; as Mr Brocklewood mocked Jane Eyre (inferring how wicked the little girl was): “This child is worse than many a little heathen who says its prayers to Brahma and kneels before Juggernaut!” It wouldn’t do to ascribe much credit to heathens you deem inferior, and if it so happens something they produce is manifestly sophisticated, it might be particularly inconvenient.

Other possible reasons Sanskrit Hindu dramas are considered by some to not be performance-worthy are:

i) Lack of familiarity with Sanskrit literary conventions.

ii) Getting too serious about the common usage in Sanskrit of elaborate stock metaphors that actually have comparatively short English equivalents.

iii) A deficiency in the right contextual understanding of Indian belief systems and philosophy. (Which is possibly where Arjundas comes in!)

iv) Last, but by no means least, not having access to an 1899 Monier Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English dictionary.