A true genius admits that he/she knows nothing.

So said Albert Einstein. It would appear that the greater learning possessed by someone, the more humble that someone is inspired to be. The learned orientalist Max Muller (above) remarked on how impressed he was by the manner in which the “Hindoos” of colonial India cooperated with the Europeans occupying their country:

I feel bound to say, with hardly one exception, they have displayed a far greater respect for truth and a far more manly and generous spirit than we are accustomed to even in Europe and America. They have strength, but no rudeness … when they were wrong, they have readily admitted their mistakes; when they were right, they have never sneered at their European adversaries.

India: What Can It Teach Us? F. Max Muller

The ignorance of the British (now a legacy) was that while intent on steeling the fabulous Koh-i-Noor diamond, they disregarded the wealth of wisdom of India’s truly humble people.

Social scientists of today are reluctant to give much serious credit to the attitudes and world views of ancient India. In many cases, they might condescend to expound on these ancient writings with metaphorical interpretations. It appears that an unconscious bias against the merits of such ancient naratives prevails. In the case of India during the British Raj, there was a very conscious, proactive effort undertaken to demerit the credibility of India’s philosophy and faith in order to justify colonial rule as being a charitable campaign to enlighten the backwardness of ‘simple’ South-East Asians.

Interestingly, the ancient Greek culture is highly regarded by western academics and nostalgically referred to as the birthplace of western civilisation. One could cynically argue that the academics who can afford to lavish praise on the merits of ancient Greeks culture, are unlike the orientalists at the time of the British Raj, who were charged with trying to dismantle ancient Indian wisdom and culture so that the colonial invasion could pass itself off as a philanthropic mission, rather than be known as the murderous, thieving, plundering outfit it actually was.

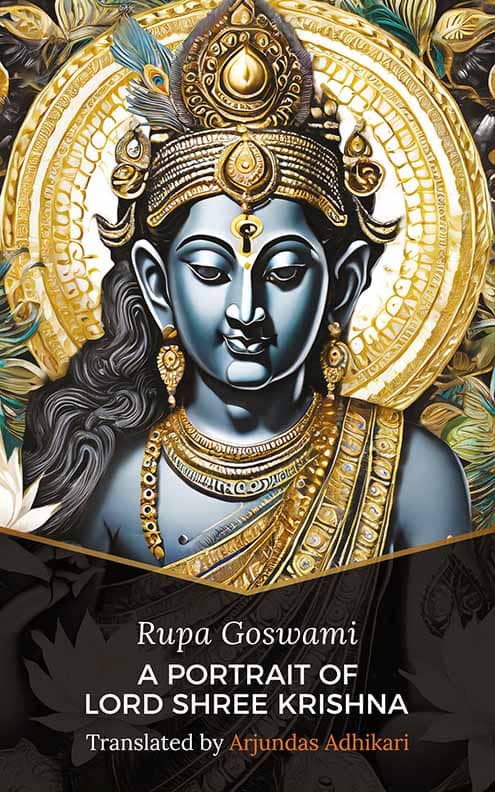

Naturally, therefore, it is unsurprising that a great Indian Sanskrit drama such as A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna, AKA Vidagdha Madhava by Rupa Goswami has been overlooked by dramatists and scholars of social science. It seems that the thoroughness and diligence applied by academics to glean an informed understanding of the cultured ancient Greeks, fades away when it comes to appreciating the fundamentals of ancient Indian culture. And the tragedy of the politicisation of any branch of the humanities is the way in which the politicised version of a given subject is inculcated into the educational system over a protracted period, and inevitably takes on an unchallenged status.

Regarding this translation of Vidagdha Madhava into English by myself, Arjundas Adhikari, I would ask any reader, student, dramatist, or progressive, whose curiosity has been peaked, to approach this Indian spiritual drama with an open mind, and judge its merits/demerits on that basis. It is not a sentimental piece. It is not an amateur’s work, and this translation attempts to capture its original spirit. Rupa Goswami certainly does not represent Shree Krishna as a character such as might be found in a half-baked pantomime (which is, unfortunately, the way I’ve seen Him misrepresented in other versions of Vidagdha Madhava translated into English). Rupa Goswami was a dramatist of the highest calibre who well-knew the characters of his spiritual creation, A Portrait to Lord Shree Krishna, and portrayed them in 3-D technicolour, as it were, by means of the finest word-smithery.

Arjundas Adhikari