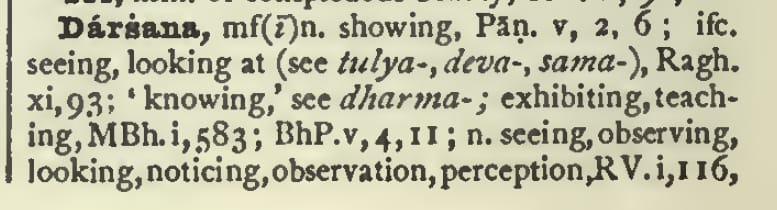

In Sanskrit, the word for ‘beholding’, or ‘seeing’, is darshan:

As is clear in the above entry taken from Monier-Williams’ 1899 Sanskrit-English dictionary, the word darshan is indicative of ‘seeing’ in the sense of ‘perceiving’ as well as ‘observing’. Sight is generally limited to a certain range of light frequencies and the availability of sunlight, or something derived therefrom. Then again, of course, one also ‘sees’ things in one’s mind’s eye, and ‘beholds’ something in a dream.

Probably the most internationally famous of the ancient Indian scriptures is the Bhagavad Gita (‘Song of God’). Bhagavad Gita is the narrator Sanjaya’s account of Krishna’s conversation with His despairing warrior friend Arjuna. Interestingly, Sanjaya was not physically present at the talk, but by the power of his third-eye vision, he witnessed the whole conversation despite being in a different location. Sanjaya was thus party to all the Truths (tattvas) revealed by Krishna to His friend Arjuna, culminating in Krishna’s confidential tattva that love for Krishna lies dormant within everyone. The means for reviving the love was also noted by Sanjaya as easily come by in the company of someone who is already tattva-darshan, i.e. beholding the Truth, i.e. someone who has already realised Krishna.

For the open-minded, and also from what is alluded to in books like Bhagavad Gita, the idea that there is a lot more to seeing, witnessing, observing, perceiving etc. than what superficially meets the eye, is not a curious notion. For the open-minded, and those acquainted with the perspicacity of the writings of Truth-seers (tattva-darshan-ers), that Truth (tattva / Krishna) is realisable, perceivable, cognisable and audienceable, is wholly acceptable. The idea that the prerequisite for beholding Krishna Himself, in person, is (metaphorically) to have eyes smeared with the salve of love, is also a more than satisfactory one:

premanjana-cchurita-bhakti-vilochanena

Brahma-samhita 5.38

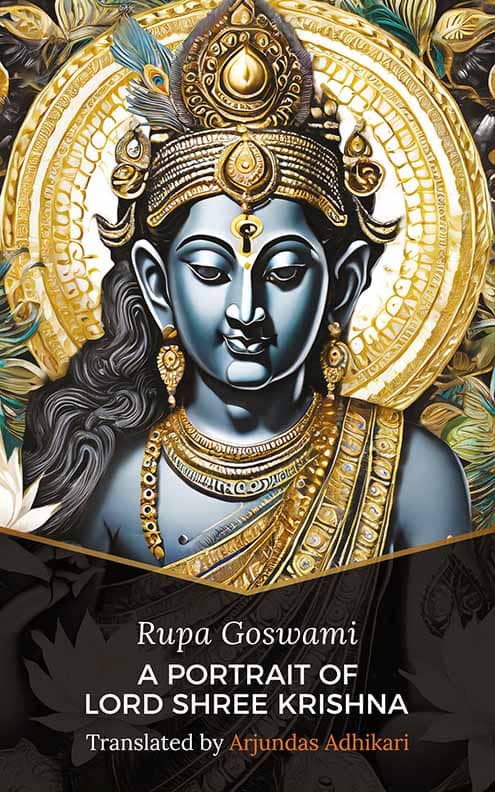

Forerunners in the line of those aspiring for personal association with Krishna assert that the behaviour of anyone actually increasing their devotion for Shree Krishna isn’t tainted by fruitive endeavours and speculative imaginings. As a leading professor of Sanskrit scripture, Rupa Goswami brings this point to the fore, reiterating that the upshot of authentic love for Krishna goes concurrently with jnana-karmaady-anavritam, that is, a lack of interest in fruitive activity and cerebral meandering. True to form, Rupa Goswami himself lived the life of an ascetic, owning very few possessions, and it’s very important to note that in authoring the spiritual drama, Vidagdha Madhava, aka, A Portrait of Lord of Lord Shree Krishna (translated into English by Arjundas Adhikari) he certainly had no ambition to get on a medieval-India bestseller list! A poor fund of knowledge about the character of Rupa Goswami and the cultural tradition he upheld and was part of, accounts for all kinds of unfortunate notions. Most importantly of all to note, though, is that the pastimes portrayed in Rupa Goswami’s Vidagdha Madhava are not products of a speculative imagination. That assumption might well prevent one experiencing something truly out of this world!

Sanjaya personally witnessed Shree Krishna advising His dear friend Arjuna, and faithfully relayed that exchange, even though Sanjaya was not physically present at the time. It is a similar kind of divya-drishti (divine vision), that enabled Rupa Goswami to personally witness the transcendental pastimes of Krishna and Radharani in Vrindavan, and share them with us in his great spiritual drama Vidagdha Madhava, aka, A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna.

Arjundas Adhikari