The rules for structuring a Sanskrit drama such as Vidagdha Madhava, or, A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna by Rupa Goswami, are steeped in antiquity. The handbook for Sanskrit drama production, called the natyashastra, was compiled by the sage Bharata in 200 BCE, and this extensive treatise starts by describing its premise, and also the history of its origin, as follows:

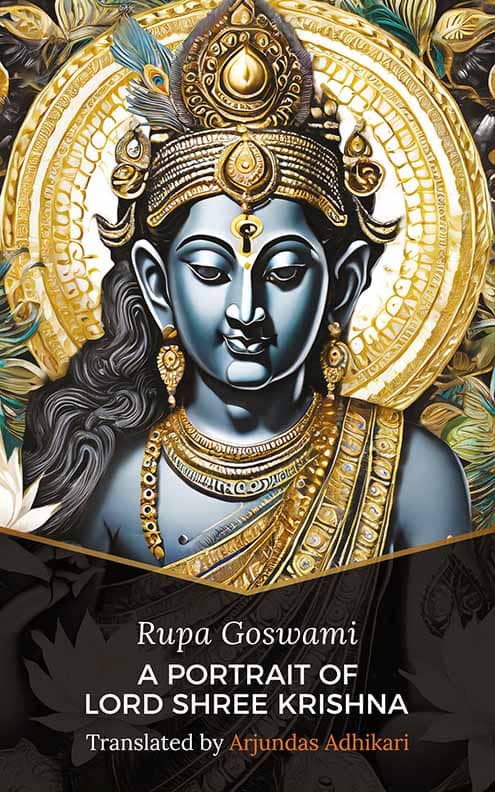

Concerned with the disadvantages the current age might impose on any opportunity for spiritual advancement, the gods once approached Brahma [pictured], their chief: “We want an object of distraction,” they declared, “the four books of knowledge – the four Vedas – are unapproachable today, because the people are too swayed by desire and greed. They’re too trapped by jealousy, too easily moved to anger, and the little happiness they do possess is too mixed with sorrow. We believe a suitable means of being benefited is now required, something both audible and visible.”

Upon deliberation, Brahma came to the following conclusion: “I shall set out a fifth Veda outlining the dramatic arts (natya) that shall be themed upon the ancient histories of the world. This fifth Veda will promote the benefits of duty, be conducive to people’s prosperity and repute, and encourage everyone to pursue activities for their long term welfare and to exercise prudence in their deeds and actions. It will also embellish the teachings of the other four Vedas.”

The dissemination of this treatise on dramatic arts, this fifth Veda, known as the natyashastra, was then entrusted to the sage Bharata, its purpose further specified by Brahma; “The dramatic arts will take into account the acts of the godly and the ungodly,” he announced, “there shall be no exclusive representation of either the gods or the demons because it shall represent the status quo of the world as it is. In it, there will need to be all kinds of references – references to duty, of course, but also to pastimes, to money, to peace, to laughter, to fighting, to love-making and to killing also. It will strengthen the sense of duty in those resolved to it, encourage whoever is pursuing the fulfilment of love, chasten the ill-bred, give courage to cowards, energise the heroic, inspire self-restraint in the disciplined, enlighten those of meagre intellect and provide insight to the learned. Dramas will be both suitable diversions for kings and means to strengthen the minds of those afflicted by sorrow. They will give ideas for economic growth to those who seek riches, and bring composure to persons agitated in mind.”

Brahma continued: “Rich in a variety of emotions, and set in a variety of situations, drama, as I have devised it, will consist, in essence, of mimicry of the actions and conducts of people. The good, bad and indifferent will be able to relate to this, and it will be a suitable vehicle for their amusement, encouragement, gladening and enlightenment. The actions, induced emotional states, and sentiments arising from drama, will be instructive to all.

“Finally,” Brahma continued, “dramatic arts shall give relief to the unlucky, be conducive to long life, to the intellect and to the general good. As I have devised it, no wise maxim, learning, skill or art is not to be found therein … mimicry of gods, demons, kings and men of this world is called drama. When human nature with its joys and sorrows is thus represented through gestures and the like, it is called drama.”

Natyashastra 1.10-121

Arjundas Adhikari