Lord Shree Krishna is referred to by numerous titles in both of Rupa Goswami’s Sanskrit plays, namely Vidagdha Madhava, a.k.a. A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna, and Lalita Madhava. In the space of only a few exchanges of dialogue, Krishna may be referred to by a number of different names. The following nine names for Krishna, for instance: Piccha-mauli, Danujarey, Ballavendra-nandana, Vrajendra-suta, Kamsa-dvisha, Kamsarey, Damodara, Ballava-mani and Hari, all occur in the few lines of speeches from 17 to 34 in Act 3 of Lalita Madhava. Piccha-mauli means He who wears a peacock-feather crown, Danujarey means He who is the enemy of demons, Ballavendra-nandana means He who is the son of the King of the cow-herdsmen, and Ballava-mani means He who is a jewel among cowherds. All these are terms of endearment – names that refer to an especially heroic deed, or a charming attribute of Krishna’s, but it must be said that without being familiar with all the legends of Krishna, the meaning of such references may well be lost on an audience. While these would have been names of Krishna familiar to a cultured Indian audience of the 16th century, many of them would not be recognised by a modern English-speaking audience, new to the culture.

In A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna, Krishna is often called Murari, Madhusudana and Murghan, after His heroism in defeating the ferocious demons Mura and Madhu. Krishna’s conquests, in this regard, do not feature in A Portrait of Lord Shree Krishna, and recognising Murari (‘The Enemy of Mura’) or Madhusudana (‘The Slayer of Madhu’) as a name of Krishna, would require a familiarity with the particular Sanskrit literatures that tell of these victories (separate from the drama itself). To make sure an English-speaking audience can follow Rupa Goswami’s Sanskrit drama, I generally revert to ‘Krishna’ (‘all-attractive’) wherever a special term of endearment replaces His name, and ‘prince’ wherever a name that conveys His heroism replaces His name.

This brings us again to the issue of translating Sanskrit in general, and the kind of initiative needed to render the right meaning. I genuinely have great admiration for the scholarship of some translators of Vidagdha Madhava and Lalita Madhava, but up to this point, I have yet to come across any English-language versions of these Sanskrit dramas that are intelligible.

Below is an example of the translation of text 19 from Act 3 of Lalita Madhava, by a Sanskrit scholar whose credentials as a Sanskrit grammarian are not contested. The intelligibility of his English, however, leaves something to be desired. In the following speech, Radha has come across a berry necklace that appears to have been dropped by Lord Krishna:

Radha. [Retrieving the gunja necklace.] Reflecting the splendour of the king of jewels, you were once on the chest of Krishna, the enemy of the demons. O gunja-necklace friend, why do you, overwhelmed, now roll about on the ground of this forest-path?

(bold font added)

Verbatim, this passes as a translation. But it is an unintelligible translation.

Beginning with the question of what the ‘king of jewels’ is, the answer’s that Krishna usually wears a splendid jewel on His chest called the kaustubha. Next to this ‘king of jewels’ around Shree Krishna, the necklace of shiny red berries Radha has found (gunja berries) would have glimmered brightly. A moderately edified audience would not necessarily know about Krishna’s kaustubha jewel.

To say the berry necklace Radha has found was ‘once on the chest of Krishna’ suggests this occurrence happened a long time ago, or that it was worn by Krishna only one time. This is not consistent with how these specific kind of berry necklaces are involved in many of the scenes of Rupa Goswami’s play, and how they are mentioned frequently as something Krishna loves to wear.

Then there is the question of how it could be that this berry necklace is ‘overwhelmed?’ Here ‘overwhelmed’ has been used for the Sanskrit word akula, but the idea in reality is that the necklace is ‘out of its natural condition.’ ‘What’s this necklace doing on the floor, when it’s normally around Krishna’s neck?’ is Radha’s query.

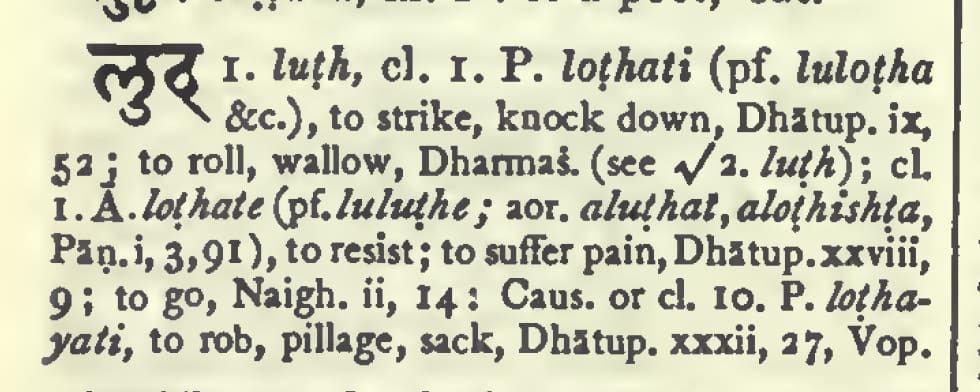

Regarding the necklace’s ‘rolling about’, it would only be doing so if something or someone were moving it. (How it could be rolling about because of being ‘overwhelmed,’ is anyone’s guess.) Mistranslation of the Sanskrit word lutha is to blame here. Although lutha can mean to ‘roll about’, in this case it is more a question of its having been ‘knocked down.’

Thus:

Radha. [Retrieving the berry necklace.] Right pretty!

Berry necklace of His chest – you who reflect the prince’s jewellery;

How is it that you end up lying on the arbour-floor?

Lalita Madhava, Act III text 19

makes more sense.

Arjundas Adhikari